In the Name of our Fathers

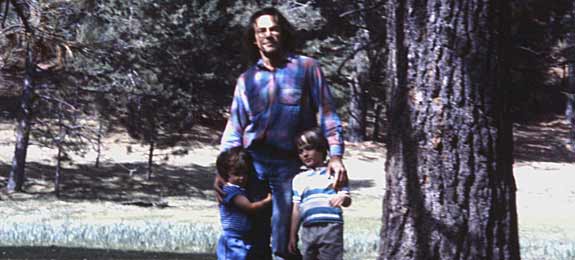

It was a cold, windy day on the grassy plains overlooking a beach in San Francisco. The wind filled sails and people sat bundled up, pretending it was a summer afternoon. San Francisco had that effect on people. It was anything they wanted it to be.

My father jogged over to a payphone, pulled a quarter from his pocket and rang my mother. “It’s such a beautiful day. You should bring the boys down here. And we can fly some kites. It’s perfect.”

“Stephen, the boys are with you.”

That was the day my mother had a talk with us about what to do if we ever got lost, though it was more for my dad than for us. His chemically-sourced absentmindedness was an origin to many stories that started more or less in this way.

Mom’s directions were simple. Find a responsible adult. Learn your phone number. Learn your address. Learn to dial “911.” Times were much different. Technology wasn’t as suffocating and the news every-hour-on-the-hour coverage about scary abductions, though the “stranger danger” mantra was fast becoming a common phrase.

In hindsight, those instructions for our urban life as two young boys seem rather liberated. Loose. They were important enough to remember, which we did, but almost unsafe when compared to the guidelines most of us have now.

Today, I am confronted with something I could not anticipate before I became a father. Now that my son is one of those kittens that you cannot herd, at the tender age of four years-old, I have to teach him about being lost and finding his way.

However, this lesson isn’t what confuses me. It’s the response to a question I posed on our Facebook page and my personal profile:

“Who do you tell your kids to seek out if they get lost?” Simple enough, right? Not really. Some of the answers are just frustrating. Out of nearly 120 comments (ruling out the obviously humorous or ridiculous ones), more than half of commenters said some version of “FIND A MOM.”

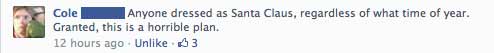

Here are some of the responses:

![]()

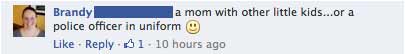

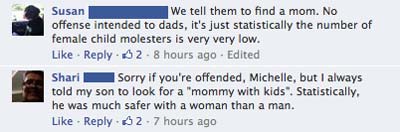

Okay. Yeah. Those weren’t helpful. How about these:

![]()

![]()

Don’t get me wrong, I understand. A whopping 96% of assaults are committed by men. I’m not telling anyone to stop saying “find a mom” here. That works for me. In fact, it’s smart. Moms are parents. Parents with kids would intuitively be the right choice. But are we stigmatizing men and fathers in so doing? Even just a little bit?

I’m not saying men don’t commit these crimes. That’s not it. I’m saying our actions can be informed by statistics, but our attitudes must be guided by context. The location, the people in question and the specifics pertaining to the form of the moment are all crucial details that, if unobserved, keep us generally fearful of others. Especially, and unfortunately, based on their race or sex.

In the end, I’m asking you to look at this in a different light, from the point of view of a man who deeply and unabashedly loves his children, and, by proxy, any child who is in need. As my friend Whit said:

“I explained that the problem with teaching children that men are bad is that some of them might actually believe it “” children that have fathers and brothers or those that will someday be men themselves. It was a terrible and ignorant weight to put on a child.”

I’ve had women ask me, sharply albeit inquisitively, which child was mine at the playground. I’ve had random, uninvited kids climb all over me and seen the eyes dart in my direction, watching my every move as I sheepishly try to stop them from making me a human jungle gym. It’s unacceptable that I couldn’t be a safe person to help a child in need, and that the odds aren’t perceived as in my favor.

This isn’t an edict but a simple request for an adjustment in how we look at keeping our children safe as told by a child who endured the very thing we’re talking about now.