A Love Letter to the Outsider

Loud and mercurial, my son is a blurry shade of all-over-the-damn-place on the plastic play structure of a park we’ve never visited before. He stomps and cheers, climbs and slides. He is my One Man Army. And I am not embarrassed for him. It’s part of what makes him so great.

But children can be cruel. A boy decides to declare war on my Finn.

Rather than stepping in, which every muscle fiber and sinew in my body is calling out for me to do, I fall back. I want to see how Finn deals with it. The old me would’ve jumped in as referee but I am now testing myself, as much as I am my son. Are we both patient enough to let things play out? I want him to develop a sense of human negotiation and observation, two skills of mine that have fallen into disrepair over time.

I am his muzzled guardian and flawed teacher.

The assailant boy becomes a semi-benign dictator and leverages the other kids to flee Finn. He makes a game out of it. It’s a full-on kid mutiny. Finn gives chase to the Kiddie Stalin and his posse, seeming to enjoy his power of control over a flock of eight other kids, but he doesn’t see how mean they are being to him. They say cruel words, do cruel things and look at him with cruel eyes. Is it bullying? I don’t know. But my son has enough energy to keep up. And more.

Finn arm-cannons a handful of sand. Now, I intervene. “That is not okay, Finn.” It comes out of my mouth a bit sharply from a distance. A few other parents look at me like I’ve lost my mind. I probably have. But what’s it to them? I haven’t slept in three years. Finn looks over sheepishly. He knows throwing sand at people is unacceptable. He’s thrown it at kids and had bucketfuls thrown in his mouth and eyes. He should know better based on both sides of the experience.

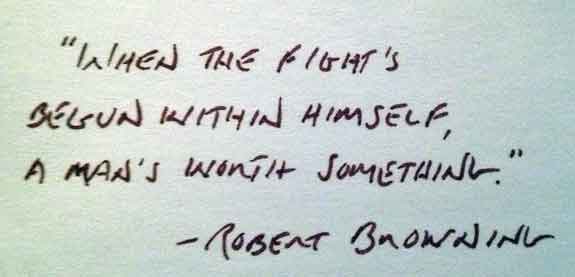

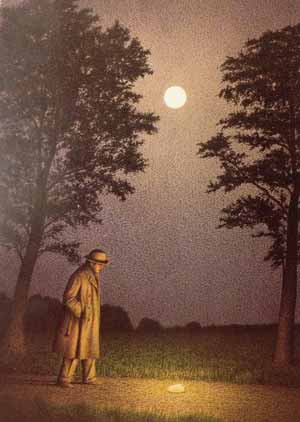

The postcard my dad sent me. When most were looking into the sky, he was looking to the ground.

The postcard my dad sent me. When most were looking into the sky, he was looking to the ground.“It’s not to okay to throw sand. You do it again and we leave, understand?” He gets it. But it’s hard. The kid pushed him first. And then Finn fired sand on him. Who’s to say who loses in this situation of assured mutual self-destruction exactly? Finn walks toward me to explain, but the young Mussolini counters by sauntering over to protect his fellow henchman, the space invader. “He pushed me,” Finn says. “I saw that. That’s not okay either. But neither of you are using good manners.” Every fiber of my fatherhood wants to tell him he’s right to stand up for himself, something we’ve talked about before, but this is a lesson about mutual destruction.

The dictator blurts out, “He’s just jealous.” Pardon me while I suppress the urge to say adult expletives to an 8-year-old. “He’s not jealous. You did something he didn’t like, kid.”

That’s as far as I go. I’m not accustomed to being a diplomat in a land of varying ages, intellects and maturity levels. I don’t believe you should punish someone for something they don’t understand, if you can help it. The boy walks away and Finn wants to join him. I could stop my son from choosing that route, vilifying the boy aggressor, but, I want Finn to recognize that he has the power of choice over who he follows. If I tell him not to go play with the boy, he may not realize that himself.

Finn takes up with the crowd again. I can’t protect him from every poisonous person in his life and I won’t prove anything by parachuting in for every skirmish, but I damn well better teach him to observe people for who they truly are and how they treat others. I see the ebbs and flows of his desire to be part of the crowd. I know those feelings, too.

My father’s words above didn’t make sense to me when he scrawled them on a postcard in 1996 for my birthday. They mean a whole lot more now. They’re prescriptive. We should all be a little bit of an Outsider. It helps us make up our own minds.